Circular farming in the city

For episode 19 of ESG (Even Samen Gevat) Marloes and Aldert went to see Minke and Peter van Wingerden. They’re the initiators of the Floating Farm, an urban farm that floats in the harbour of Rotterdam

Minke and Peter argue in favour of disruption and a radically different approach – of ‘having the courage to think and do things differently.’ As far as they’re concerned, that goes not only for farming but also for the climate. Because the only way to achieve change is to think outside of the box. Minke calls that ‘Making bigger ripples in the pond by throwing in one small stone.’ What makes the Floating Farm a good example of that? What was the thinking behind this initiative?

What is the Floating Farm?

The first thing you notice about the Floating Farm is that it’s no traditional farm with large stretches of pasture land but rather a floating platform in a harbour. The complex has three levels. ‘The best level is for our cows, of course’, says Minke. The cows, 36 in total, live on the top floor, but they can also walk out onto a small ‘back pasture’ if they feel like being outside for a little while: ‘the only patch of green in the whole harbour area.’ A processing floor is located under the cowhouse. That’s where, for example, the milk, manure and the feed for the cows are processed and the captured rainwater is purified. A robot is used to collect and process the manure. It separates that into dry and wet manure, which produces less emissions. The lowest level of the Floating Farm is all peace and quiet, as nature does its work. That’s where the cheese ripens that’s made from the farm’s own milk, for example, and there’s also an installation for vertical farming, where they’ve been experimenting with growing basil, lettuce and mint.

The Floating Farm is also a shop where people from the neighbourhood can buy products like butter, cheese, raw milk, buttermilk and yoghurt. ‘That’s going well’, says Minke. In addition, the shop also sells products from farms and community initiatives in the neighbourhood.

Why a floating farm in a city?

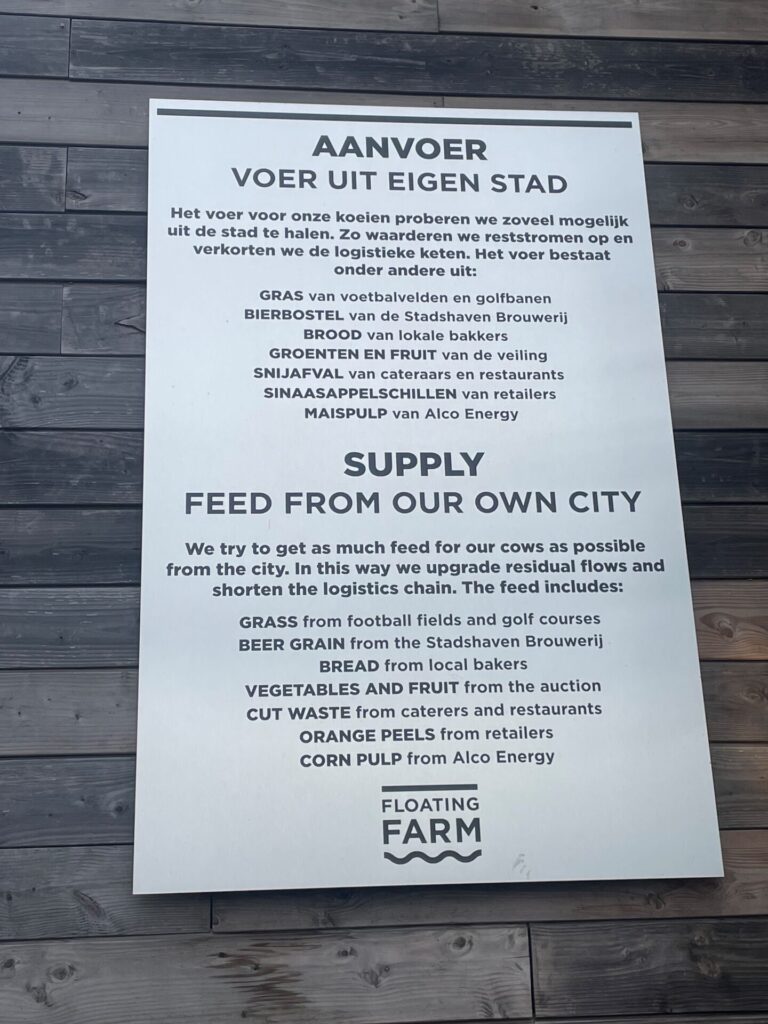

One of the aims of the Floating Farm was already stated above: circularity and processing refuse flows from the city. Such as bread, orange peels and beans from Ethiopia that can’t be sold any more. ‘Valuable nutrients are burnt every day’, says Peter. Burnt in incinerators, that is to say. That’s the destruction of food that can be used to feed animals. ‘We take that food refuse and extract proteins that go back to the city.’

Another goal is to reduce transport that’s bad for the environment. ‘Our society is totally dependent on transport for its food supply’, says Peter. You can do something about that by producing food closer to consumers. He got that idea during a stay in New York. Hurricane Sandy was sweeping across the city at that time, with wide-spread flooding: ‘People were very afraid; all panic broke out.’ Since transport was not possible, people had no way to get food. So Minke and Peter thought: ‘Why don’t we make floating and climate-adaptive food. No matter how high the water rises, how much rain falls, we can always make the things that are important.’ Especially when you realise that many cities are situated by the water.

The third goal is animal welfare. ‘The cows here can walk from inside to outside and vice-versa’, says Minke. ‘The most important thing for a cow is really good bedding’, says Peter. ‘A cow spends about 14 hours a day lying down and resting and chewing the cud. And they spend about six hours eating and drinking. So that’s 20 hours of the day. And thanks to the milk robot, the cows can be milked all the time. That makes them really happy.’ So it’s not like cows want to spend the whole day leisurely grazing in a pasture, as many people think and as some marketers would have us believe.

That brings us to the fourth goal of the Floating Farm: to create greater awareness. Minke: ‘We get a lot of visitors who have no clue where the milk comes from or how our food system works.’ For instance, many people don’t realise that products which come from far away are sometimes cheaper than local products. ‘True pricing really needs to made part of climate policy.’

The final goal is ‘harmony among people, plants and animals. It’s vital to bring that back to the city. That’s what the world was once like, and that’s how it needs to be again’, says Minke.

Is the Floating Farm idea catching on?

The concept of the Floating Farm has been getting a lot of attention worldwide. Before COVID we received 60 to 70 groups a month from all over the world’, says Peter. ‘From Japan to the USA: students, government ministers, farmers, architects, urban planners.’ And that’s not surprising, because every city is struggling with the same problem: ‘How am I going to feed my people in a healthy way and in the context of climate change?’

The Floating Farm can be seen as a shining example. ‘Why should more and more land be turned into concrete because those people need to be housed in the city?’ Nevertheless, the concept has yet to be copied anywhere else in the world, which makes the Floating Farm a unique initiative – at least for now.

“We have to tackle those rules, because radical change is what we need. We need a system change and the only way to do that is with people who think completely differently and come from another sector to bring change“

Peter van wingerden

What’s next?

In the meantime, Minke and Peter are busy with the design of version 2.0 of the farm ‘where we’re looking at not only the circularity of the food flows but also the circularity of energy and circularity of heat and cold.’

The idea is also to build a second floating farm with vertical farming with fruit and vegetables. But it’s not going to be easy: the laws are a huge obstacle for these kinds of initiatives. That was evident even when developing the current farm. ‘Obtaining a licence takes years.’ Peter gets frustrated by that: ‘Society has become a big jumble of regulations. To break free, we need to do something radically different.’ There it is again: radical change. ‘We have to tackle those rules, because radical change is what we need’, says Peter. We need a system change. To him, the only way to do that is with people ‘who think completely differently and come from another sector to bring change.’

“True pricing really needs to made part of climate policy”, according to Minke van Wingerden

ESG Even Samen Gevat is a podcast series (in Dutch) in which Aldert Veldhuisen and Marloes Bergevoet talk to accelerators of the sustainable transition. They discuss topics related to the “E”, like green energy, CO2 emissions, raw materials, biodiversity, the “S” of health, diversity and inclusiveness and the “G” such as laws and regulations and international cooperation.

Also published in this series are:

- 100 conversations about sustainability – with Marnix Kluiters

- Circularity is hip – with Klaske Kruk

- There is life after growth – with Paul Schenderling

Follow Even Samen Gevat here so you don’t miss an episode!